CHAPTER XIX

HOMELAND DEFENSE: STRATEGIC SETBACKS

AND FINAL PREPARATIONS

Air Raids and the Industrial Crisis

From the very beginning, preparations for the defense of the Homeland had been seriously hampered by enemy air activity over the home islands.1 Shortly after the Ketsu-Go plan had been issued, these attacks were intensified and rapidly reached a point at which they threatened to disintegrate the entire social and economic structure of the nation before the decisive battle could even be begun.

From the standpoint of physical destruction and suffering, the worst raids of all were the B-29 incendiary attacks against urban areas. During April, May, and June, the fire-bomb campaign against the large urban complexes was mercilessly continued. In June, it was extended to 12 small and medium-sized cities containing important basic materials and sub-contracting facilities.2 In some of the larger raids it was estimated that as many as 400 B-29's participated, while the monthly cumulative total of B-29 sorties rose by June to 3270.3

Carrier planes, as well as fighters and bombers from Okinawa and Iwo Jima also added weight to the attacks. Although these were mainly directed at airfields in Kyushu, urban areas as far east as Tokyo were harassed by strafing and bombing. Fighter and bomber sorties from Okinawa reached a monthly total of 777 by June and fighter sweeps from Iwo Jima 265 for the same period.4

The damage caused by these operations was almost incalculable. Large areas of the three urban complexes forming the keystones of Japan's war economy were laid waste, 56% of the Tokyo-Kawasaki-Yokohama area, 52% of Nagoya, and 57% of Osaka-Kobe being burned out causing complete paralysis of production, transportation, and communications facilities. Key industrial installations in the smaller cities were also levelled. Harbors and channels all along the Japan Sea and the Inland

[613]

Sea were tightly sealed with aerial mines for days at a time. It became almost impossible to move material or commodities either from the continent or between ports in Japan itself.5

By the end of June, about 118,000 citizens in the three major urban areas had met with violent and painful deaths, about 170,000 were wounded and missing, about 1,300,000 buildings had been destroyed, and a total of 5,503,000 persons, about 42% of the population of Japan's three largest urban areas had been bereft of their homes, furniture, clothing, and personal effects.6

These violent assaults on the very foundations of urban society were rapidly reflected in the morale, efficiency, and availability of the labor force. The attacks so aggravated the already precarious food situation and created such a critical shortage of housing that millions were forced to flee to the countryside to seek the very necessities of life. In Tokyo-Kawasaki-Yokohama, for example, 4,210,000 people, about 53% of the population evacuated, leaving the remains of their homes and their means of livelihood behind. Throughout the nation more than 8,000,000 persons did likewise, meaning that almost 10% of the national citizenry became displaced persons.7

The mass evacuations greatly compounded the effects of the air raids on productive capacity. Immediately following the raids, an absentee rate of 70-80% was noted, dropping to about 40% after the restoration of local order. Even in those factory districts not damaged, the rate was about 15%. This high rate of worker absenteeism was an important factor in the decline of industrial productivity.8

The evacuations were symptomatic of the steady disintegration of organized urban life. Against the overpowering enemy air offensive the people and their local officials were beginning to feel completely helpless. The entire system of air raid precautions simply collapsed under the unexpectedly heavy assault. Shelters proved insufficient in number and vulnerable to enemy bombs, fire-fighting equipment was entirely inadequate to cope with the cascade of incendiaries, and the welfare, medical, and rehabilitation programs were over-saturated by the flood of casualties and

[614]

homeless refugees.9

Although the dislocation of urban society was bad enough, a much more serious long-term result of the air raids was their effect on the industrial plant of the nation. Prior to April, the submarine and mine blockade, combined with the air attacks of November 1944 through March 1945, had carried forward apace the disintegration of Japanese basic industry which had begun early in 1944.10 During the spring and early summer, this process assumed alarming proportions.

The most critical shortage continued to be that of coal. By June 1945, the imports of heavy coking coal from North China had ceased, crippling heavy industry. Although the domestic production of coal held up fairly well,11 it proved to be almost impossible to move it in any appreciable amount due to the submarine and mine blockade of the major ports.12

The coal shortage fell most heavily on the iron and steel, non-ferrous metals, cement, and chemicals industries. By the end of June, the production of ferrous metals (iron, steel, and carbon steel had fallen to a mere 35% of the wartime peak. Cement production was down to 46% of the peak figure.13 The situation was no better in critical non-ferrous metals, with copper, aluminum, and magnesium standing at a bare 35% of the industry's peak, and in one case, that of aluminum, sagging to a disastrous 16%.14

The chemicals industry, like the others, was

[615]

PLATE NO. 150

Air Raid Shelter

[616]

hard hit by shortages of raw materials, a special problem being the scarcity of salt.15 In the case of five selected chemical products (ammonia, nitric acid, caustic soda, benzol, and toluol) total production in the quarter ending in June 1945 was only 43% of the same period in 1944.16 The most important immediate effect of the collapse of the chemicals industry was on the production of explosives. The gross production of propellants, high explosives, and primer materials in June 1945 was only 62% of the peak established in March 1944.17 This made it exceedingly difficult for the Japanese to meet the ammunition production program laid down to support decisive battle plans.

From the standpoint of decisive battle planning, the most dangerous basic material shortage was that of oil.18 By the end of June, the quarterly gross national production and import of crude and refined petroleum had fallen to 24% of the wartime peak established in the period July-September 1943, and the inventory of 4,751,000 barrels was only about 8% of what had been on hand at the beginning of the war.19 Of this, only about 606,000 barrels were aviation gasoline, of which 333,900 barrels were earmarked for decisive battle operations.

Despite a reduction in operations to within 80% of expectations, including rigid curtailment of training flights and elimination of all operational flights except those connected with the continued prosecution of Ten-Go,20 consumption still ran about 188,600 barrels in June against a production of about 98,000 barrels.21 Although aviation gasoline was to be supplemented by alcohol and other substitute fuels, the projected margin between requirements and

[617]

inventories was so exceedingly narrow that, particularly if the enemy continued to bomb refineries and tank farms, it was doubtful whether the decisive air battle could be fought later than the end of 1945.22

By the end of June, the decline of basic industry had not yet had its full impact on the fabricating industries of Japan. Although they were producing substantially less than they had at peak output, it was felt that the majority of decisive battle needs could be met by the estimated time of invasion. Aircraft production held up best of all, a total of 4,856 aircraft of all types being manufactured in the quarter ending in June. This was 65% of the wartime peak rate.23

The munitions industry was, at this time, somewhat less well off than aircraft, and the production goals set to support decisive battle plans seemed beyond reach in most items.24 This industry had reached its peak in the period October-December 1944 and thereafter fell off mainly as a result of raw material shortages. By the end of June 1945, Army ordnance industries were producing at a rate of only about 44% of peak and Navy facilities at about 55%.25

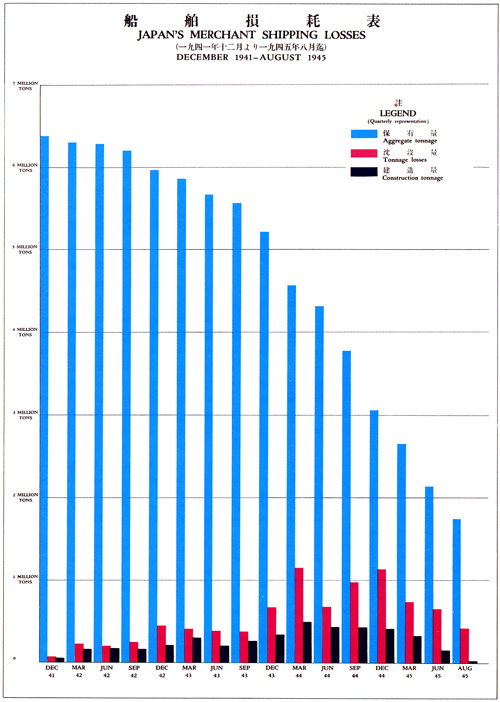

The shipping industry was also caught in the vicious circle of raw material shortages and high attrition through losses.26 By the end of June, 79% of all Japan's merchant tonnage had been sunk. Shipyards were producing a bare 27% of the wartime peak set in January-March 1944. Maritime shipping capacity was down to 850,000 gross tons and was dropping at the rate of 2,300,000 tons per month. In the quarter just ended cargo loading amounted to 2,968,400 tons or roughly 27 % of wartime peak maritime activity. The shipping crisis was severe enough to dash any hope that industry could even be partially revived through efforts to improve the raw material situation.27

The blockade and the air raids had the same

[618]

impact on the service industries as elsewhere. Of these, by far the most important was food. Before the war, Japan imported about 20% of her most important staple, rice, from Korea, Formosa, and the southern area. The shipping shortage had reduced this to a trickle, no rice at all being imported from the southern area after March 1944. The ambitious program of subsisting the nation on continental imports, which had been laid down in January 1945,28 fell far short, only 60% of the quota being met in the quarter January-March and even less by June. Moreover, rice for the Armed Forces had been withdrawn in ever increasing quantities so that, by 1945, there was on the average 40% less rice for civilian consumers than had been the case in 1941. An even worse situation obtained in the case of soy beans, meat, fish, vegetables and salt.29

As a result of the dwindling inventories of basic foods, the daily ration amounted to fewer than 1,500 calories, about 65% of the minimum Japanese standard for the maintenance of health and work efficiency.30 While this was not actually a starvation diet, the prospect of the tightening of the blockade plus attacks on Japan's land transportation system, and the possibility of attacks on the unharvested fields themselves all gave rise to a distinct danger of famine, at least in the more densely populated areas.

Even more frightening was the possibility that the U. S. invasion might be so long postponed that the troops disposed for decisive battle would run through their reserve rations. This was one more reason why an invasion in the fall was to be preferred if Japan were to strike the heavy counter-blow which she was so carefully planning.31

Progress of Mobilization

and Deployment

As enemy air raids hammered away at the threadbare fabric of Japan's industrial economy, preparations for the decisive battle were carried resolutely forward. In a series of orders issued during the first week in April, Imperial General Headquarters set in motion the second mobilization of ground troops according to plan.32 Six new Army headquarters,33 eight line combat

[619]

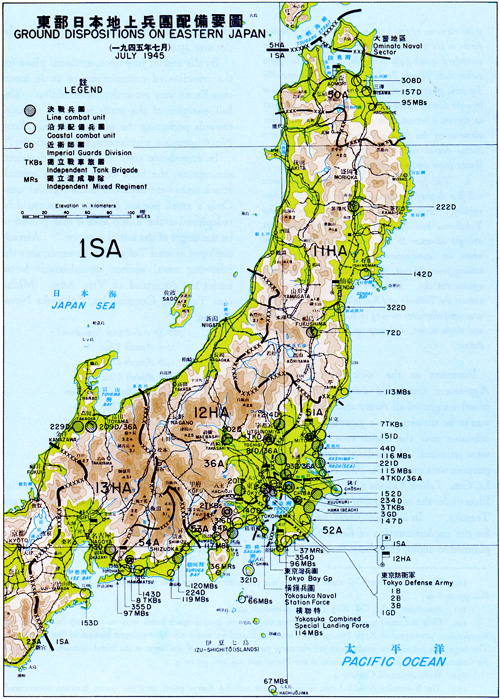

PLATE NO. 151

Japan's Merchant Shipping Losses

[620]

divisions,34 and six armored brigades were activated in the Homeland and subsequently assigned as follows:35

First General Army

Twelfth Area Army

Thirty-sixth Army36

201st Division

202d Division

214th Division

Fifty-first Army

7th Tank Brigade

Fifty-second Army

3d Tank Brigade

Fifty-third Army

2d Tank Brigade

Thirteenth Area Army

209th Division

Second General Army

Fifteenth Area Army

Fifty-fifth Army

Sixteenth Area Army

Fifty-sixth Army

4th Tank Brigade

Fifty-seventh Army

5th Tank Brigade

6th Tank Brigade

205th Division37

206th Division

212th Division

216th Division

Concurrently with this second phase mobilization, the planned diversion of troop units from Manchuria was executed.38 The 1st Armored Division began to arrive in the Thirty-sixth Army zone in early April, closing into the new position before the end of the month. The 25th and 57th Divisions, scheduled for assignment to Sixteenth Area Army and Thirty-sixth Army, respectively, arrived in Kyushu by mid-May, while the 11th Division displaced into the Fifteenth Area Army zone in southern Shikoku in early May.39 Although not called for in the original plan, the 8th Tank Brigade was also included in the redeployment and joined the Thirteenth Area Army in the Tokai district of central Honshu.40

The High Command had meanwhile undertaken a reexamination of the strategic situation in light of the increasingly unfavorable developments on Okinawa. By early May Imperial General Headquarters concluded that the enemy might soon be free to take the initiative

[621]

in the next major move and that Kyushu now appeared the more probable target, the earliest possible invasion date falling after late June.41

The possibility of an invasion two months earlier than previously estimated resulted in an immediate acceleration of the defensive preparations. The first move was the transfer, 1 May, of units from the less threatened northeastern flank of the Homeland, the 147th Division being diverted to Kanto from Hokkaido and the 3d Amphibious Brigade to southern Kyushu from the Kuriles.42

In view of the extremely remote probability of an enemy invasion of the northeastern area and of further contemplated withdrawals from this area, Imperial General Headquarters ordered the Fifth Area Army on 9 May to concentrate the bulk of its troops on Hokkaido, leaving garrisons to defend only the more important islands in the Kurile chain43 This new mission, in effect, ruled out possible activation of Kestu No. 1, and rendered any subsequent action in this area of a delaying nature rather than decisive.44

In the week which followed, the High Command further strengthened the defenses of Kyushu and its approaches with the assignment of two additional divisions and the activation of a new independent mixed brigade. The 57th Division just assembling at Hakata, Kyushu, en route from Manchuria to join the Thirty-sixth Army, was reassigned to the Sixteenth Area Army on 10 May.45 Four days later the 77th Division (Hokkaido) was transferred from the Fifth Area Army to Sixteenth Area Army while on the same day the lone infantry regiment securing the island of Tanegashima lying just South of Kyushu was reorganized as the 109th Independent Mixed Brigade.46

Concurrently with these steps taken by the High Command, the Second General Army Commander. Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, drafted an operational plan to meet the situation. This called for forces in Kyushu to wage a delaying action if the enemy should land during July, trading space for time until the assembly, equipping, and training of the decisive battle reserve could be completed and a general counteroffensive launched. Preparations for the delaying campaign in the critical invasion areas were to be completed by the end

[622]

of June.47

While the mobilization and redeployment of ground troops was on schedule the preparation of battle positions in the critical invasion areas was falling seriously behind. Although the troops were assisted by thousands of civilian volunteers, by early May the construction of coastal positions in Kyushu had barely begun. The 86th Division and the 98th Independent Mixed Brigade, garrisoning the Ariake Bay area, had brought their field fortifications to about 50% completion, while the 156th Division on the Miyazaki coast, the 146th Division on the Satsuma peninsula, and the 145th Division in the Fukuoka area were only 10-20% finished. Troops in all these units were in a low state of training,48 headquarters command arrangements were inadequate, and weapons, ammunition, equipment, and horses were still in short supply.49 In the Kanto district, an even worse situation obtained.50 There were permanent coast defense batteries in the entrance to Tokyo Bay and a few scattered semi-permanent heavy artillery positions forming the nuclei of projected strongpoints, but an effective field fortification system did not as yet exist.51

More discouraging than the lag in field construction was the extent to which local commanders misunderstood the policy of aggressive beach defense and failed properly to indoctrinate their subordinates.52 Based largely on precedents set in the southern area, many coastal combat units located their rallying positions much too far from the beach. Although this was an understandable attempt to avoid the devastating effects of enemy naval bombardment, it had the highly undesirable

[623]

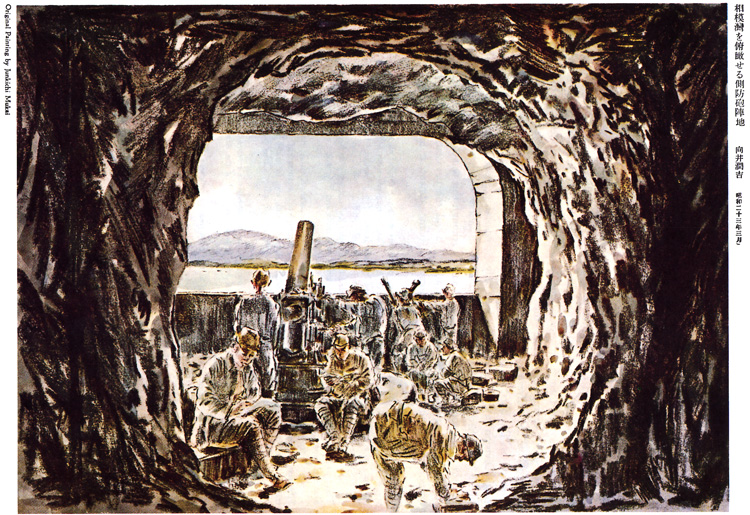

PLATE NO. 152

Flanking Gun Emplacement Overlooking Sagami Bay

[624]

effect of allowing the enemy to seize and consolidate a sizeable beachhead, which was entirely contrary to Ketsu-Go doctrine. Line combat divisions of the decisive battle reserve were also establishing their concentration points too far inland.

These discrepancies were uncovered during May by staff officers of Imperial General Headquarters while inspecting the critical invasion areas. Immediate remedial action was clearly indicated. On 6 June, therefore, the Army Section of Imperial General Headquarters issued a new manual of decisive battle tactics. This document contained an even stronger statement of the aggressive beach defense doctrine than had been laid down in the Ketsu-Go plan and its implementing directives. At the same time, the Chief of the Army General Staff, General Yoshijiro Umezu, drew up a detailed explanation of the desires of the High Command and disseminated it to all units. Pursuant to these instructions, the Commanders-in-Chief of the First and Second General Army immediately initiated strong orientation and indoctrination programs in their respective areas. However, much valuable time had already been lost.53

The lag in the construction of coastal positions, the costly misunderstandings concerning tactical doctrine, and the difficulties of redeployment and training were especially dangerous in Kyushu since it was earliest on the estimated invasion schedule. To help meet the situation, Marshal Hata, in late May forwarded a strong recommendation to Imperial General Headquarters that the forces scheduled for redeployment to Kyushu under the Ketsu-Go plan be moved immediately without waiting for activation of the operation.54 The High Command, however, was so worried about the dangers inherent in what they felt to be a premature weakening of the Kanto district that no action was taken on this recommendation.55

While the major ground commands were engaged in these preparations, Imperial General Headquarters took steps to ready the Army air establishment for the decisive battle. On 8 May, orders were issued releasing the Second Air Army in Manchuria from the order of battle of the Kwantung Army, the Fifth Air Army in China from the China Expeditionary Army, and the 1st Air Division in the Northeast area from Fifth Area Army. All these forces were assigned to the Air General Army.56

On the same day, the High Command issued a directive outlining the air redeployment plan for Ketsu-Go. The essentials of this document were as follows:57

1. Policy

Although participation in the Ten-Go operation will continue, primary emphasis will be on completing preparations for Ketsu-Go by the end of June.

[625]

2. Redeployment Outline

(a) The main strength of Fifth Air Army will immediately proceed to Korea. An element will remain in China under the command of the Commander-in-Chief, China Expeditionary Army.

(b) When an alert for the Ketsu-Go operation is issued, the main strength of the 1st Air Division will be immediately transferred to the anticipated operational area.

(c) Upon activation o f the Ketsu-Go operation, the main strength of the Second Air Army and that part of the Fifth Air Army remaining in China will be immediately transferred to the active battle theater.

(d) Should the enemy land in the China coastal sector prior to the Ketsu-Go operation, Fifth Air Army, reinforced by designated units of Second Air Army will proceed to the enemy landing area and attack. These operations will be supervised by the Commander-in-Chief, China Expeditionary Army.

By late May, it had become apparent to the Army High Command that further pursuance of the Ten-Go operation would result in a needless expenditure of air strength without appreciably delaying the enemy in his final approach to the Homeland.58 On 26 May, therefore, orders were issued releasing the Sixth Air Army from attachment to Combined Fleet and reverting it to control of the Air General Army. At the same time, General Masakazu Kawabe, Commander-in-Chief of Air General Army, was given a directive concerning his immediate mission, the gist of which was as follows:59

The Commander-in-Chief, Air General Army, will accelerate operational preparations with the main objective of destroying enemy forces invading the Homeland. Emphasis will be on the Kyushu and Korea Strait area.

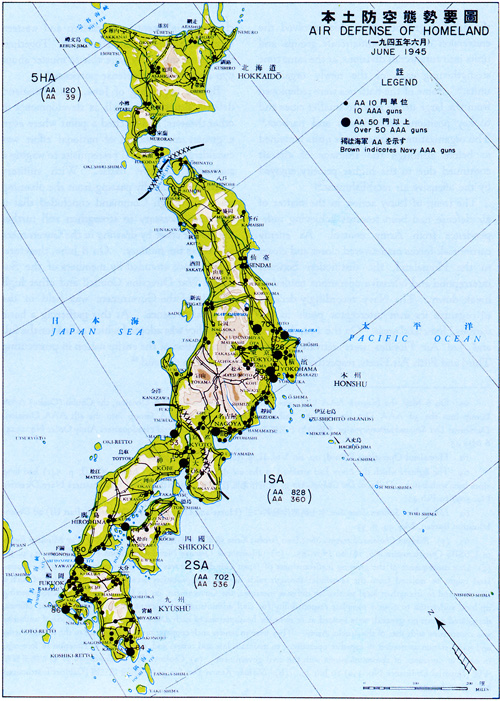

The most serious operational problem facing the Japanese remained that of air defense. In the struggle to provide an antidote to the violent enemy air offensive, the nation was handicapped by many adverse circumstances. In the first place, having lost the Marianas and Iwo Jima, and with Okinawa already being used as a forward base, the Japanese were deprived of patrol and reconnaissance bases so necessary to the maintenance of an adequate warning network. Moreover, the enemy, using these same bases was now able to mount fighter-escorted bombing attacks over almost all of the Homeland. Another serious handicap was the chronic shortage of antiaircraft guns and ammunition, brought about mainly through the decline in production of these items. Finally, it was found that even those guns that were available were ineffective against night attacks by high-altitude planes.60

In the face of these obstacles, both the Army and the Navy undertook to reorganize, strengthen, and redeploy air defense forces. In

[626]

the case of ground units, this involved the conversion of several antiaircraft groups and units into antiaircraft divisions, at the same time strengthening each of the newly organized units.61 Some of the batteries were redeployed from the large urban areas to smaller cities and to key positions on railroads and harbors.62The organization of interceptor units remained as before although the shortage of aircraft continued due to the higher priority enjoyed by the offensive air establishment.63

The trend of Navy action in the matter of air defense had been towards achieving independence from Army control. As enemy carrier task forces maneuvered closer and closer to the Homeland, the distinction between interception and offensive operations tended to break down. The Navy accordingly decided to organize its own interceptor pools in the various Homeland areas. On the 23d, the 71st and 72d Air Flotillas were activated under Third and Fifth Air Fleets, respectively, to take charge of interception in eastern and western Honshu, Shikoku, and Kyushu.64 Together, the Army and Navy were able to muster about 970 aircraft for air defense purposes.65

By the beginning of June, the Homeland defense situation, as well as developments in other theaters, had reached a point where even a greater mobilization of national effort was considered an essential prerequisite to waging a successful decisive battle. With military preparations rapidly passing from the planning stage, the High Command concluded that it was now necessary to strengthen still further the all-out effort by drawing in the Government as well as the military. On 8 June, therefore, a conference attended by members of the Supreme War Direction Council and other high officials of the Government was held in the Imperial presence. At this gathering a basic war policy was adopted which called for the full participation of the entire nation in prosecuting the war to the end.66

[627]

PLATE NO. 153

Air Defense of Homeland, June 1945

[628]

Pursuant to the decisions of the Imperial conference, the Government on 23 June promulgated the National Volunteer Service Act, which, together with its implementing directives, contained the following general provisions:67

1. National volunteer units will be immediately organized in each prefecture, each railway and communication division control district, and in designated major industrial installations, the prefecture constituting a regimental district. All men 15-60 and all women 17-40 will be subject to such service.

2. General supervision of the organization of these units will be exercised by the District Army (Area Army commander assisted by the local governor-general. Existing Civilian Defense units, Neighborhood Associations, etc., will be absorbed into the new organization.

3. Volunteer unit missions will include transportation, communications, construction, repair, and other logistics duties, security of vital installations, intelligence work, and, should the need arise, fighting beside the regular line units.

4. In general, arms and equipment will be limited to small arms, grenades, and grenade dischargers.

In the meantime, Imperial General Headquarters had taken steps to effect the third mobilization of ground combat units almost two months earlier than originally planned.68 Pursuant to a series of organization orders, the first of which was issued on 23 May, four new Army headquarters,69 10 coastal combat divisions,70 eight line combat divisions,71 and 14 independent mixed brigades were activated in the Homeland72 and on 19 June, assigned as follows:73

First General Army

Eleventh Area Army

Fiftieth Army

308th Division

[629]

222d Division

322d Division

113th Independent Mixed Brigade

Twelfth Area Army

Tokyo Bay Group74

354th Division

114th Independent Mixed Brigade

Tokyo Defense Army

Fifty-first Army

221st Division

115th Independent Mixed Brigade

116th Independent Mixed Brigade

Fifty-second Army

234th Division

Fifty-third Army

316th Division

117th Independent Mixed Brigade

321st Division

Thirteenth Area Army

Fifty-fourth Army

224th Division

355th Division

119th Independent Mixed Brigade

120th Independent Mixed Brigade

229th Division

Second General Army

Fifteenth Area Army

Fifty-fifth Army

344th Division

121st Independent Mixed Brigade

Fifty-ninth Army

230th Division

231st Division

124th Independent Mixed Brigade

225th Division

123d Independent Mixed Brigade

Sixteenth Area Army

Fortieth Army75

303d Division

125th Independent Mixed Brigade

Fifty-sixth Army

312th Division

351st Division

118th Independent Mixed Brigade

122d Independent Mixed Brigade

126th Independent Mixed Brigade

With these activations, the line strength of the Homeland defense armies (including Hokkaido) was brought to 30 line combat divisions,76 24 coastal combat divisions, two armored divisions, seven a tank brigades, 23 independent mixed brigades, and three infantry brigades.77

Concurrently with the implementation of the third mobilization, a further redeployment of major combat units was effected. The Fifth Area Army transferred the 42d Division and Chishima ist Brigade from the Kurile Islands to Hokkaido while at the same time the High Command ordered the transfer of the 4th Amphibious Brigade from the Kuriles to the Twelfth Area Army.78 In addition, the 209th Division was transferred from Thirteenth Area

[630]

Army to Thirty-sixth Army, further strengthening this large reserve Army to a total of six line combat and two armored divisions.79

By this time, production trends clearly indicated that industry was incapable of adequately supporting the immense structure of the Homeland defense forces and the tactical and strategic plans devised for their use. The priority enjoyed by the units in Kyushu was draining off almost all of the material strength of the military establishment. While this meant that preparations for the decisive battle in Kyushu would be almost certainly completed, it also meant that Kyushu would very likely be the only area in which a decisive battle could be supported at all.

The brightest spot in the otherwise clouded production picture was in aircraft. By the end of June, almost 8,000 planes, mostly tokko types, had been hoarded for the decisive battle, while it was fairly certain that an additional 2,500 could be produced by the end of September.80 Although this program was running slightly behind the schedule laid down in February,81 it remained a single encouraging item in an atmosphere of disaster. Facilities for basing this vast special-attack armada were also being rushed to completion. A total of 325 airstrips, some of which were simple one way strips, were under construction throughout the Homeland, 95 of them on secret sites far in the interior.82

Although doing fairly well in aircraft, the Japanese were far behind schedule in ground combat ordnance. At the end of June, output in every item was short of the schedule that had been set earlier in the year. Percentages of scheduled production actually achieved by this time were as follows:83

Rifles |

78% |

Light machine guns |

62% |

Machine guns |

89% |

Infantry cannon |

13% |

Antiaircraft guns |

62% |

Mortars |

8% |

Self-propelled cannon |

25% |

| Light artillery | 17% |

| Heavy artillery | 60% |

[631]

This discouraging situation in weapons production naturally made it very difficult to equip new units and almost impossible to achieve adequate levels in reserve dumps. The bulk of production was channeled to units in Kyushu and it was felt that at least sufficient weapons would be available to fight the decisive battle in that area by September.

Another bad situation facing the Japanese at this time was the extent to which preparations for naval surface participation in the Ketsu-Go were falling behind. In the quarter ending 30 June, only 1,235 surface special-attack boats had been produced and only 324 underwater types.84 These were 18% and 15% respectively of the targets set for September. While it seemed hardly likely that these goals could be met, as in the case of ordnance, it was felt that sufficient quantities would be available to fight the Kyushu decisive battle at least.

The failure of production efforts, coupled with transportation and communications difficulties, shortages of fuel and rations, and continued enemy air attacks had, by the end of June, dealt serious blows to the national preparations for decisive battle. As far as organization of units was concerned, there were few difficulties. In both Kyushu and Kanto, units of the third mobilization were expected to be fully organized, although untrained, by mid July. In Kyushu, 60% of these had already begun their training.85

Equipment, however, was another story. In Kanto, units of the third mobilization were short in every item, with no prospect of catching up as long as Kyushu held a higher priority. This was particularly true of small arms, anti-tank guns, mortars, and self-propelled cannon. Even in Kyushu, stocks of equipment on hand were only about 50% of third mobilization requirements with 31 August as the tentative completion date.86

Stockpiling of expendables was also in a confused state. In Kanto, no munitions and ordnance stockpiles had been established at all, while rations stocking was about 50% complete. Units in Kyushu, however, had built ammunition stockpiles to 100% of Ketsu-Go requirements, fuel to 94%, and rations to 164%.87 This was encouraging as regards the conduct of the Kyushu battle, but pointed up the fact that the national war potential was

[632]

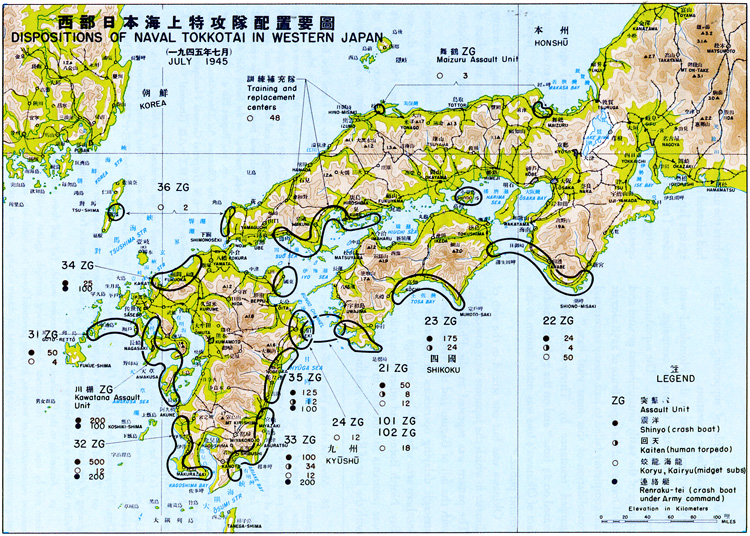

PLATE NO. 154

Dispositions of Naval Tokkotai in Western Japan, July 1945

[633]

probably incapable of supporting more than one such decisive operation.

While preparations in the Homeland went slowly forward, the Okinawa campaign was brought to its unhappy end. The superhuman courage of the vastly outnumbered ground and naval forces and the expenditure of 2258 aircraft had completely failed to halt enemy seizure and consolidation of this most vital base.88 Organized resistance by Thirty-second Army ceased on 23 June89 and on the 25th the painful fact of Okinawa's loss was made known to the general public.90

Okinawa was but one strand in the web of disaster in which the Japanese were now caught. The pattern was repeated in the Philippines with the fall of Baguio and the virtual end of strategic delaying operations in Luzon, in the southern area where Allied landings at Brunei Bay, North Borneo and other points cut Japanese remnants to ribbons, in southeast Asia with the loss of Rangoon, and finally in Europe where the unconditional surrender of Germany had released millions of troops for redeployment against Japan Against this background, President Truman on 2 June made public the basic strategy to be used in the invasion of Japan, an operation that could not now be far off.91

A New Estimate of the Situation

Being inferior in the technical equipment of war and having been forced into an extremely disadvantageous strategic position, Japan's principal hope of success in the forthcoming Homeland battle lay in outguessing the enemy in accurately predicting the time and place of the invasion and meeting it with overwhelming force.

Quick formulation of a strategic estimate was, however, rendered impossible by the existence within Imperial General Headquarters of a wide range of opinion on every aspect of the problem. The only point on which there

[634]

was general agreement was that the enemy would immediately intensify the sea and air blockade of Japan and would sooner or later attempt an invasion.

The most important of the controversial issues was whether the United States would seek an early end to the war by moving immediately, or, on the other hand, initiate a long blockade designed to reduce Japan to the point of complete helplessness.92 A dominant majority adhered to the former alternative, and it became the official position of Imperial General Headquarters.93

Proceeding on the assumption that United States policy would call for a quick decisive battle, there were two possibilities regarding the direction and objective of enemy operations. First of all, the United States might seek an immediate decision by moving directly to the main Japanese islands. In this case, the enemy might first seize air and sea bases in such areas as the northern Ryukyus and the Izu Island chain lying between Tokyo and the northern Bonins. He would most certainly drop such plans, however, and move at once against the main Japanese islands if he ever became convinced that Japanese air power had completely collapsed.

On the other hand, with Japan Proper as the ultimate goal, the enemy might first seize additional major advance bases.94 A part of the Army intelligence staff in Imperial General Headquarters, particularly those officers connected with Chinese intelligence, was convinced that the United States forces would land in central and/or north China in order to give military support to the Chungking regime. Other groups within the headquarters, particu larly in the Army operations group, held that two strong additional possibilities were an invasion of southern Korea or of Saishu (Quelpart) Island lying in the key Korea Strait area. Any of these three would gain important advance bases, would cut Japan's continental supply lines, and, in the first two cases, would check Soviet influence in north China and Korea.

[635]

These possibilities were the subject of discussion in the High Command, with the majority opinion adhering to the view that the northern Ryukyus were the most probable target with Quelpart as a possible secondary invasion area.95

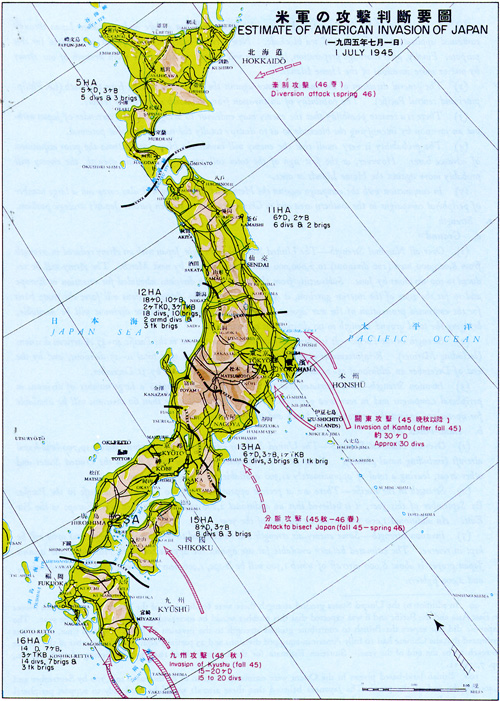

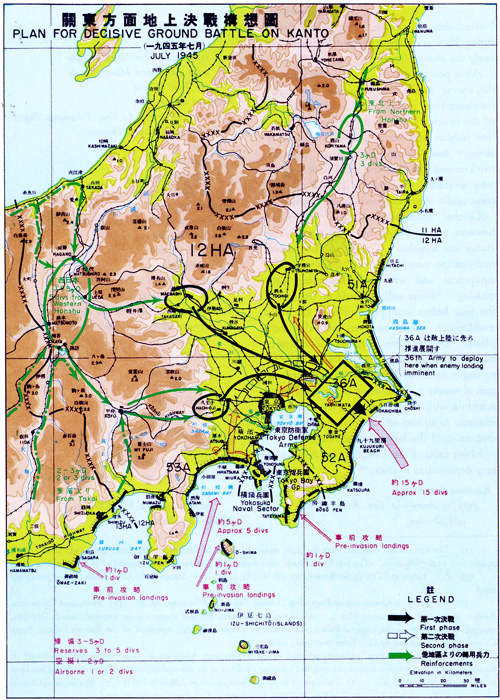

Following these preliminary operations, the enemy was expected to move as soon as possible against Japan Proper. In this connection, there were two possibilities considered, the first being a direct move to the Kanto district, and the other a campaign to gain air and sea bases in Kyushu and Shikoku first, followed by an advance on Kanto. While there was considerable anxiety over the possibility of a direct attack on Kanto,96 a great majority of the officers in Imperial General Headquarters agreed that the invasion of Kyushu seemed most probable.97 In any case, the consensus was that, so long as Japan was resolved to resist to the end, the final battle would be on the plains of Kanto, since it was not only the political and strategic center of the nation, but also the most favorable area for the deployment of enemy armored and mechanized equipment.

The various opinions concerning enemy capabilities and intentions were contained in formal estimates, memoranda, and other communications that circulated in High Command circles from May to July. Each idea was considered for acceptance or rejection by the Chiefs of the Army and Navy General Staff. No written estimate, however, was ever produced representing the combined opinion of the highest command levels. The study and circulation of the basic documents resulted, nevertheless, in the formulation of an official position that represented a blend of all the accepted recommendations and provided a firm basis for future action. A detailed summary of the final estimate is as follows:98

1. Over-all Strategy

a. Strategic Objective: The enemy's objective is to bring the war to an early end by securing the unconditional surrender of Japan.

b. General Method:

[636]

PLATE NO. 155

Estimate of Allied Invasion, 1 July 1945

[637]

(1) In pursuance of his fundamental objective, the enemy will first isolate and neutralize Japan through continued application of the air and sea blockade. New forward bases will be acquired and utilized for this purpose. Finally, after thorough preparation, the enemy will attempt to destroy the main strength of our Army by one or more invasions of the Home Islands.

(2) The general direction of the enemy advance against the Homeland will be from the south (i.e. Philippines and central Pacific). The possibility of an invasion from the north is extremely remote.

(3) There is a remote possibility that the enemy may endeavor to bring about the surrender of Japan without an invasion by intensifying the blockade so as to destroy totally the national combat potential.

(4) The probability is very small that the enemy will invade the Homeland without the prior acquisition of advance bases. However, at the first sign of the total collapse of Japanese air strength, the enemy will probably move against the Home Islands at once.

(5) In conjunction with the campaign against the Homeland, the enemy will also carry out a large number of peripheral campaigns in the southern area and in China, designed to weaken further Japan's strategic position.

2. Strength

a. Ground 99

(1) Over-all National Strength-The United States plans to fight Japan with an Army reduced in strength from 8,000,000 men (120 divisions) to 7,000,000 men (103 divisions) by next March. The Army will be reduced to 100 divisions by June. Subtracting from this figure the 10 divisions scheduled for retention in Europe and 10 for the zone of the interior garrison, it appears that about 80 Army divisions will form the troop basis for the continued prosecution of the war against Japan. In addition, 10 Marine divisions will be available, bringing the total ground strength to 90 divisions as of June 1946.

(2) Strength in the Pacific. It is estimated that there are at present in the Pacific 40-45 American divisions (including Marines). Reinforcements expected to arrive by September 1945 total 10-15 divisions, and by the end of December an additional 15-20 divisions. Total: 65-80 divisions by 31 December.

(3) Invasion Strength-It is estimated that the United States will employ a large number of divisions in peripheral campaigns and in rear area garrisons. Consequently, not more than 60 divisions will be available for operations against the approaches to Japan and the Homeland itself.

b. Land-based Air100

(1) Over-all National Strength-The United States is estimated to have approximately 19,700 land based aircraft (including naval planes). About 3,600 are stationed in Europe and 4,800 in the United States and other areas, leaving a total of approximately 11,300 available for use against Japan.

(2) Strength in the Pacific-There are at present approximately 8,500 land-based aircraft in the Pacific. By September of this year, it is believed that an additional 2,200 will be redeployed from Europe to the Far East. An additional 1,000 will arrive by the end of the year.

(3) Invasion Strength-Some enemy air strength will be diverted to peripheral campaigns and some will be kept in reserve. The estimated balance available for use against the approaches to the Homeland and against Japan proper is about 6,000 aircraft of which 1,500 will be B-29s, 1,400 heavy bombers, 1,100 medium bombers, and 2,000 fighters.

[638]

c. Carrier Air 101

(1) Over-all National Strength-Present U. S. carrier air strength is estimated at 2,100 aircraft. This will be expanded to 4,100 by September, 4,800 by the end of the year, and 5,100 by next spring.

(2) Strength in the Pacific-Present fleet carrier air strength in the Pacific is about 1,600.

(3) Invasion Strength-A small number of carrier aircraft will remain stationed in the Atlantic. A large number will be used for miscellaneous duties in the Pacific such as convoy escort, training, and supporting peripheral operations. Deducting all these activities and those held for repair and replacement, it is estimated that 2,400 planes will be available by September, 2,600 by the end of the year, and 3,100 by next spring for use over the approaches to the Homeland and against Japan itself.

d. Naval Strength102

(1) Over-all National Strength-The estimated over-all composition of the United States Fleet by the end of December is 32 aircraft carriers, 85 escort carriers, 21 battleships, 58 cruisers, and 450 destroyers.

(2) Invasion Strength-It is estimated that 25 carriers, 25 escort carriers, 21 battleships, 54 cruisers, and 330 destroyers will be available for operations on the approaches to the Homeland and against Japan itself.

3. Targets

a. Preliminary Operations

(1) In order to intensify the sea and air blockade and to prepare for future operations against Japan proper, the enemy will seize advance bases during July and August.

(2) An advance into the northern Ryukyus and the Izu Islands is most probable. Strengths committed will be: (a) To the northern Ryukyus (Toku-no-Shima, Kikaiga Jima, and Amami Oshima), 1-2 divisions, and (b) to the Izu Islands, 1-2 divisions.

(3) As an additional possibility, the enemy may advance into the coastal sector of central and/or north China. Strategic areas to be attacked are, in the order of probability, the Ning-po-Shanghai area and southern Shantung Province. Commitment to this enterprise will be about 10 divisions. If scheduled, this operation will have the additional purpose of giving political and military support to Chungking and checking the advance of Soviet influence in China.

(4) Two additional possibilities are an invasion of Quelpart Island or southern Korea. One of these operations is less probable than either of the above, although Quelpart may be invaded as an extension of the enemy's program in the northern Ryukyus outlined in (2) above. Commitment to this operation will be about 6 divisions.

b. First Mainland Attack

(1) Due to the fact that it is the political and economic center of the Japanese Empire as well as the best tactical terrain in the Home Islands, the enemy will fight the final decisive battle with the Japanese Army in the Kanto area.

(2) Contingent upon the availability of shipping, the enemy can mount a 30 division operation, or any series of operations involving a cumulative total of 30 divisions, by late fall of this year. He can mount a 50 division operation, or any series of operations involving a cumulative total of 50 divisions, by next spring.

(3) In order to prepare for the final decisive battle in the Homeland, the enemy will desire to secure additional forward sea and air bases to cover his approach to Kanto.

(4) Following the preliminary operations, the enemy will attempt to secure advance bases by a large-scale

[639]

amphibious lodgement in the southern part of Japan proper. Targets will be Tanega-Shima, southern Kyushu, and the south coast of Shikoku. A commitment of 15-20 divisions is anticipated. This operation can be mounted any time after September contingent upon no commitment to the China mainland.103 If the China operation is executed, the Kyushu operation cannot be mounted until after late fall.

(5) It is possible that the enemy may seek to open a decisive battle in Kyushu. If so, the operation will be executed in late fall with about 30 divisions. Targets will be southern Kyushu and the Hakata Bay-Shimonoseki-Moji area of northern Kyushu. This operation has a very low degree of probability. It cannot occur at all this year, if the enemy commits any strength to the China mainland.

c. Main Invasion

(1) Upon completion of his operational objectives in southern Japan and assembly of the necessary strength, the enemy will invade Kanto. This operation may be covered by a diversionary feint at Hokkaido. Commitment to the operation will be about 30 divisions and it will be mounted next spring.

(2) If it becomes apparent to the enemy that Japanese air power has completely collapsed, he will launch a direct invasion of Kanto late this fall, using about 30 divisions.

(3) If the enemy tries a blockade operation (See 1 (b) above), which fails to force Japan to surrender, a direct invasion of Kanto with go divisions next spring is a very remote possibility.

4. Allied Participation

a. Participation in the Homeland invasion by Allies of the United States is expected to be little more than token in nature, with the single exception of the British Pacific Fleet. However, the Allies are expected to engage in a variety of peripheral operations designed to weaken further the Japanese strategic position. It is believed that the enemy plans a consistent policy of coordinating his operations in China and the southern area with those against the Homeland.

b. Southern Area

(1) Great Britain undoubtedly plans to recapture Malaya and Hongkong, to complete the reoccupation of Borneo, and to bring Thailand within her sphere of influence. The British will also seek to occupy areas of military importance in the Netherlands East Indies and French Indo-China.

(2) Burma-Malaya Area-The enemy will probably open a general offensive in Burma with the front line strength now available there (about 11 divisions). If this operation meets with success, amphibious operations will be launched against the southwest coast of the Malay Peninsula and thence south by shore-to-shore bounds, the final target being Singapore. The initial lodgement will be secured during July or August with 3-5 divisions, and the total commitment to the operation will be 9-12 divisions. A limited objective operation against the northwestern tip of Sumatra is probable in order to secure air bases and cover the flank of the drive toward Singapore. Simultaneous overland invasion of central and southern Thailand with 4-5 divisions is expected.

(3) Indo-China-A composite force of approximately five American, French, and Australian divisions will probably enter southern French Indo-China in the summer or early fall.

(4) Netherlands Indies-The reconquest of Borneo will be completed using 3-5 divisions. The probability of an invasion of Sumatra, Java, and the Lesser Sundas is very small. If the redeployment of Dutch troops proceeds satisfactorily, the enemy may launch a 2-3 division operation in that area next year. Meantime, the area will be neutralized by air and naval bombardment.

[640]

c. China Area

(1) The enemy will employ 3-5 divisions in landings on the south China coast, most probably in the Canton-Hongkong sector but possibly in the Hainan Island-Luichow Peninsula area. Upon completion of operations in south China, these forces may enter northeastern French Indo-China.

(2) Chungking will open a general offensive not central China in July or August, utilizing mainly American-equipped and trained troops.

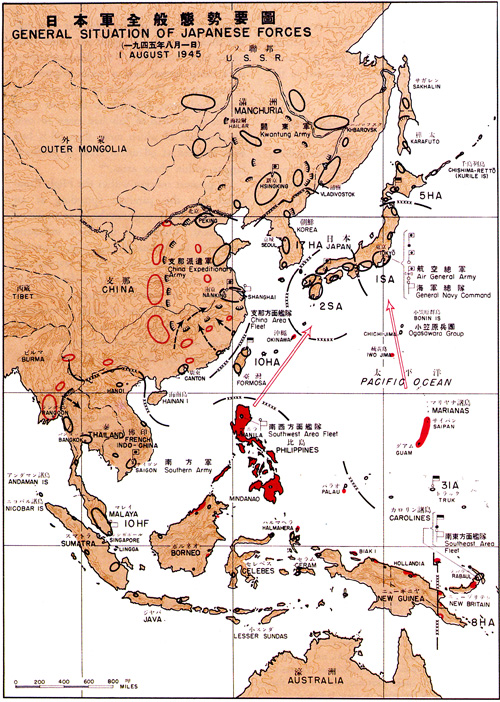

5. The Soviet Union

a. Since the Soviet Union announced its intention to abrogate the Russo Japanese neutrality pact, it has been heavily reinforcing its military strength in the Far East. Since mid-February the estimated reinforcement has amounted to about 550,000 troops, 3,700 aircraft, 2,000 tanks, 6,700 field pieces, and 13,400 motor vehicles. Present strength is about 1,300,000 troops, 5,400 planes, and 3,000 tanks.

b. The Soviet Union, lit order to further its political objectives lit the Far East, will probably enter the Greater East Asia War at the earliest opportunity.

c. If the present reinforcement rate continues, the Soviet Union will be capable of commencing military action against Japan in August or September.

6. Evaluation

a. The enemy is mustering enormous and overwhelming military strength for use against Japan, and the issue will be joined between now and next spring.

b. Although Japan is faced with an exceedingly precarious strategic situation, there are certain circumstances that are working to her advantage.

(1) While the end of the war in Europe has given the United States a comfortable reserve of national war potential, industrial mobilization and reconversion have already begun due to the desire to grab quick post-war profits.

(2) The fighting morale of the United States is being weakened by the fear of large casualties.

(3) There has been an increase in labor strife, criticism of the military, and agitation from the ranks to engage in a precipitous demobilization.

c. Should the United States be defeated in the battle for Japan itself, public confidence in the President and the military leaders will decline abruptly, fighting morale will deteriorate in the flurry of recriminations, and Japan will be placed in a much more favorable strategic position.

On 5 July, the Navy Section of the High Command formally abandoned its concept of the decisive air battle over the East China Sea, the Ten-Go air operation having long since deteriorated into a series of small scale hit-and-run raids.104 The way was now clear to the formulation of a joint Army-Navy Air Agreement for the Ketsu-Go operation, an annex that had long been missing from the basic plan.

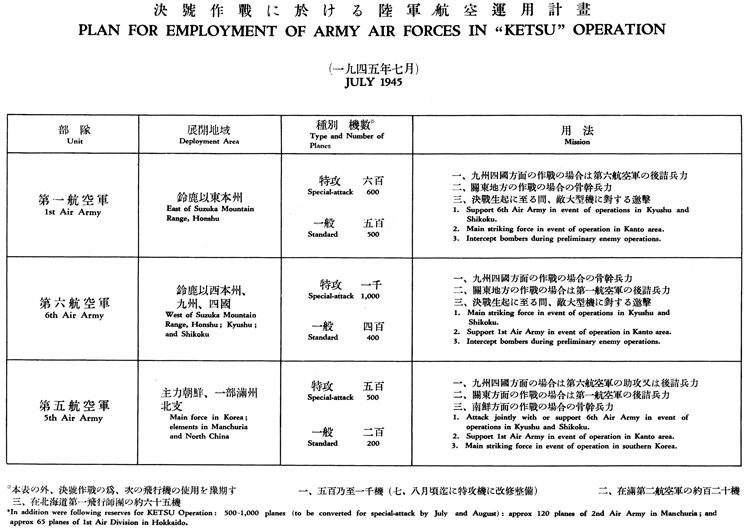

This agreement was issued to the field on 13 July, its basic features being as follows:105

1. Missions

a. The primary mission of the Army and Navy air forces will be to locate and destroy the American expeditionary force while it is on the water. Emphasis will be placed on special-attack operations.

b. Secondary missions will include:

(1) Air defense

(2) Anti-submarine operations

(3) Air attacks to delay the enemy preliminary operations against the approaches to the Homeland.

[641]

PLATE NO. 156

Plan for Employment of Army Air Forces in Ketsu Operation, July 1945

[642]

(4) Air attacks on enemy carrier task forces.

(5) Tactical support of defending ground troops.

2. Outline of Operations

a. Theater

(1) Operational preparations will be completed in full in Kyushu, Shikoku, and southern Korea.

(2) Preliminary preparations will be completed for possible action in other Ketsu-Go operational areas especially Kanto.

b. Operational Concept-Primary Mission

(1) Reconnaissance of enemy advance bases is essential in order to obtain warning of the enemy approach.

(2) First priority target will be enemy transports.106

(3) The landing convoys will be attacked and destroyed at the first stage of the landing (i. e. during about the first ten days).

c. Operational Concept-Secondary Missions

(1) The Army will operate its fighting strength as economically as possible, engaging in short, opportune interception operations against enemy heavy bombers. Both services will cooperate in staging long range hit-and-run raids against enemy heavy bomber bases in the Marianas, Bonins, and on Okinawa.

(2) The Navy will intensify anti-submarine operations in the Japan Sea area by clearing the waters and preventing further penetration.

(3) A part of the fighting strength will be utilized to inflict casualties and delay enemy preliminary operations against the China coast, the northern Ryukyus and/or Bonins, the Izu Islands, Tanega-Shima, Goto, Quelpart, and/or southern Korea. Such operations will be mounted only by locally available forces, and they will not be allowed to compromise the conduct of the Homeland decisive battle.

(4) Enemy carrier task forces will be attacked with a part of our strength for the purpose of interdicting tactical air support o f the enemy landings.

(5) In rendering support to the ground effort, the main emphasis will be on attacking enemy gunnery ships engaged in shore fire support. Such attacks will be synchronized with the local offensive activities of the ground units.

3. General Development and Strength

a. Initial dispositions (Plates No. 156-157)

(1) In western Honshu, Shikoku, Kyushu, and Korea will be stationed the Fifth and Sixth Air Armies, the Fifth Air Fleet, and a part of the Tenth Air Fleet.

b. A total commitment of all available air forces will be made in the area in which the enemy first invades Japan, most probably Kyushu. Over-all strength committed will be as follows:107

(1) Army: 3,200 aircraft

(2) Navy: 5,225

4. Command Relationships

a. The general basic command relationship will be one of inter-service cooperation.

b. Commanders of major air commands will be stationed at the same locations or as close as possible to their respective opposite numbers. Command posts for the decisive battle will be chosen immediately.108

[643]

Tables appended to this agreement indicated in detail the desired deployment of all available air strength.

As the summer wore on, many complex planning difficulties arose in high-level Japanese headquarters, the most important of which was brought about by the shift of operational emphasis to Kyushu. It was feared that the high priority accorded to preparations in the south would so drain off field engineering supplies, ammunition, food, fuel and lubricants, and all other classes of military supplies that it would be impossible to conduct properly the defense of Kanto should that area be attacked directly before the end of the year.

A second source of anxiety to the High Command were the shortcomings of Japanese strategic intelligence. This was largely a result of the drying up of the major sources of information. With both air and sea superiority lost right up to the very shores of Japan itself, direct and frequent observation of enemy invasion bases by Japanese submarines and planes was impossible. The High Command was forced to rely almost entirely on radio intelligence, although this means was not completely reliable, and certainly not so in determining absolutely the direction, time, and strength of the attack. This inability to get sufficient warning naturally compounded the anxiety that was being felt about Kanto.109

In addition to these worries, the month of July found Imperial General Headquarters increasingly concerned about the possibility of an enemy landing in the Tokai (Nagoya) district of central Honshu. From the very beginning, the High Command had believed in the remote possibility that this area would be selected as a target.110 This feeling now became particularly strong in view of the fact that the Tokai district was the narrowest part of Honshu, that its defenses were relatively weak, and that with both Kyushu and Kanto becoming stronger day by day, it might tempt the enemy to cut Japan in two by landing in the vicinity of Ise Bay and occupy the areas around Nagoya, Kyoto, and Osaka. On 20 July, a staff group from Imperial General Headquarters held a special meeting in Kyoto to discuss countermeasures.111

A fourth troublesome problem faced by the High Command was the weakness of the defenses of Manchuria, northern Korea and Karafuto. Despite indications that the Soviet Union was on the verge of commencing hostilities against Japan, the Kwantung Army, already weakened by the withdrawal of troops and munitions for the Philippines, Formosa, and Okinawa, had been further reduced by the diversion of four crack divisions to the Homeland.112 Having decided on all-out commitment against the forthcoming American invasion attempt, there was little that Imperial General Headquarters could do about this particular problem except hope that the Japanese units could hold off the Soviet tide while a decision was being sought in the Homeland.113

[644]

PLATE NO. 157

Plan for Employment of Navy Air Forces in Ketsu Operation

[645]

Still another problem which caused considerable concern within the High Command was the critically weak coastal defenses along the Japan Sea side of the Homeland. Recognizing that Japanese sea and air forces could not deny the enemy use of the vital Korea Strait, Imperial General Headquarters and Second General Army took some steps during July to strengthen the defenses along the coast of western Honshu.114 This flank, nevertheless, remained extremely vulnerable.

Far more serious than even these strategic planning problems was the extent of the damage inflicted on Japan by enemy aircraft during the month of July. After the devastation of March through June it seemed almost impossible that the American air offensive could gain in intensity. Such was far from the case. During the month, the Japanese counted a total of 20,859 sorties flown over the Homeland by enemy aircraft, more than four times as many as in any previous month. Only six days in the month were free of air raids of any kind, and on one day (28 July) more than 3,400 sorties were flown.115

During July, B-29 operations against the Homeland were expanded about 25%. Abandoning the offensive against large urban areas, the enemy concentrated his July attacks against 35 small and medium-sized cities, each of which received more than 100 tons of bombs, mostly incendiaries, and fourteen of which received more than 1,000 tons.116 At the same time, the aerial mining campaign against Japan's coastal waterways was continued.

During the same period, other enemy air forces were far from idle. Okinawa-based bombers and fighters swarmed all over southern Japan piling up a total of 3,193 sorties, almost four times as many as in June. Fighters based on Iwo Jima, operating mainly over the Kanto, the Osaka-Kobe, and Nagoya areas, flew 1,787 sorties, almost seven times as many as in the previous month. Both these short-range air forces hammered air bases, shipping factories, railroads, tactical positions, and even fishing villages throughout all of Japan west of Tokyo. Air reconnaissance activities over Kyushu, Shikoku, and Kanto were even more pronounced than in June.

About 10 July, the American carrier task force appeared again, hitting targets throughout Japan, but concentrating on Hokkaido and northeastern Honshu. These atttacks, directed mainly against airfields, shipping, industrial targets, and transportation, added up to a total for the month of 12,213 sorties.117

Urban area incendiary raids continued to cause the deepest and most lasting damage to the Japanese war potential. Large sections of the cities which contained some of Japan's most vital fabricating and sub-contracting facilities lay in smouldering ruins.118 Next in importance were the enemy carrier task force

[646]

raids. Vital steel production facilities at Ishin omaki, Kamaishi, and Wanishi were heavily damaged in these operations. Widespread havoc was wrought in the ports of Aomori and Hakodate, the most serious loss being the putting out of action of every single one of the rail ferries plying between Hokkaido and Honshu. This cut rail haulage capacity between the two islands from 300,000 tons per month to almost zero. The carrier plane campaign against Japanese airfields throughout the Home Islands continued, interdicting many important installations and heavily damaging several.119

Even before the July raids, it had become obvious that an unchallenged continuation of such mass enemy air attacks would render Japan physically incapable of further resistance, particularly if the enemy shifted, as appeared likely, to attacks on the nation's land transport system and other tactical targets. To meet this situation, the High Command took a drastic step. On 30 June, Imperial General Headquarters ordered Air General Army to assume complete responsibility for carrying out a systematic air defense of the Homeland, simultaneously transferring the 10th, 11th and 12th Air Divisions, which had been engaged in air defense operations under the control of respective area armies, to the command of the Air General Army. This new mission represented a switch from the former policy of strict conservation of aircraft.

Operations were carried out during July but, in spite of the addition of eleven fighter regiments to the air defense forces,120 units were still so thinly spread and quick concentration was so difficult, that enemy air units continued to break through almost at will.121

In the midst of these discouraging planning

[647]

and operational setbacks, the only encouraging sign remained the fact that the forces on Kyushu were rapidly reaching a state of full combat readiness. Regardless of what appeared to be disaster for the Japanese nation, the High Command held firm in its resolve to fight the Kyushu battle as scheduled.122

Preparations for the Defense of Kyushu

The responsibility for preparing the ground defenses of Kyushu belonged to Field Marshal Shunroku Hata, Commander-in-Chief, Second General Army and, under him, to Lt. Gen. Isamu Yokoyama, Commander of Sixteenth Area Army. Pursuant to the basic Ketsu-Go plan, the headquarters of both these officers as well as the staffs of the local army commanders had undertaken to estimate the trend of future enemy tactics to be used against Kyushu. By early July, these efforts had resulted in a consensus of opinion which was substantially as follows:123

1. General Objective

The general aim of the enemy invasion of Kyushu will be to destroy the Japanese forces on the southern Kyushu front and immediately occupy, important sea and air bases in Miyazaki and Kagoshima Prefectures.124

2. Preliminary Operations

a. The enemy will continue all-out attacks with strategic air and naval forces in order to maintain the blockade, annihilate Japanese air strength, and destroy the nation's domestic communications.125

b. The enemy will invade Tanega Shima and install a forward fighter base there to support the main landing.

c. Just prior to the main landing on Kyushu proper, the enemy may make a short feint in another area to conceal the real invasion goal.

d. The main landing will be preceded by several days of concentrated shelling and bombing attacks against coastal positions and installations in order to neutralize air bases, knock out fortifications, destroy communications, and isolate the proposed battle area.

3. Main Landing

a. It is most probable that the main attack will be directed against the Ariake Bay and Miyazaki coast areas with a secondary attack against the west side of the Satsuma Peninsula.

b. In coordination with the main amphibious effort, it is highly likely that the enemy will drop strong airborne forces on the group of airfields around Kanoya, Myakonojo, and Nyutabaru.

c. Simultaneously with the operations against Kyushu, it is highly probable that the enemy will attack southern Shikoku.126

[648]

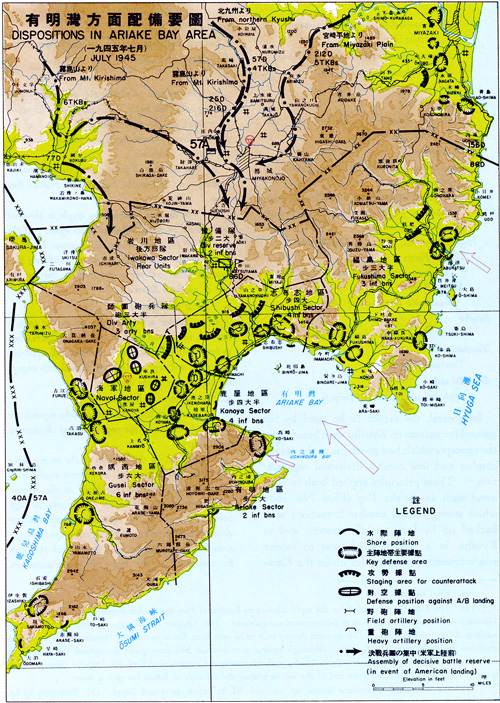

PLATE NO. 158

Ground Dispositions on Western Japan, July 1945

[649]

4. Strength

a. The enemy will use approximately 15-18 divisions in this operation.

b. Enemy strength will be distributed as follows:

Ariake Bay-5-6 divisions

Miyazaki coast-3-4 divisions

Satsuma Peninsula-2 divisions

Shikoku-2 divisions

Airborne-1-2 divisions

Army reserve-1-2 divisions

5. Post-Landing Tactics

a. Forces landing in the Ariake-Bay area will occupy the Kanoya sector, the coast of Kagoshima Bay, and later the Miyakonojo area. Elements of this force will seize the Mt. Kirishima area.

b. The force landing on the Miyazaki coast will occupy the Miyazaki plain, the Karasebaru, and the Nyutabaru airfield sector. Part of this force will be sent rapidly forward to the Miyakonojo sector to aid the advance of the Ariake Bay landing force.

c. The force landing on the Satsuma Peninsula will occupy Chiran and Kagoshima city. Some elements will secure a line roughly along the boundary between Kumamoto and Kagoshima Prefectures.

6. Northern Kyushu

a. There is a remote possibility that the enemy may seek an all-out decisive battle in Kyushu, including, in addition to the operations in the south, an amphibious invasion of the northern part of the island.127

b. Probable landing areas include the Fukuma sector (main landing and the Hakata and Kokura areas (secondary landings). In order to cover this operation the enemy will also seize Quelpart or the Goto Islands.

c. The objectives of this operation will be to occupy the Shimonoseki-Moji area covering the vital Tsushima and Shimonoseki Straits. Airfields on the Hakata and Kurume Plains will be overrun, while elements will drive deep into the island to block reinforcement from the interior.

It was the Japanese intention to blunt the enemy invasion spearhead off Kyushu chiefly by an all-out attack of the air forces. Immediately available in western Japan for this purpose were units of the Sixth Air Army under Lt. Gen. Michio Sugawara and of Fifth Air Fleet under Vice Adm. Matome Ugaki. These were as follows:128

Sixth Air Army

11th Air Division

12th Air Division

30th Composite Air Group

51st Air Division

6th Fighter Brigade

100th Fighter Brigade

27th Torpedo Bomber Brigade

Fifth Air Fleet

72d Air Flotilla

203d Fighter Group

332d Fighter Group

343d Fighter Group

352d Fighter Group

12th Air Flotilla

12 unnumbered tokko groups

634th Reconnaissance Group

701st Bomber Group

762d Bomber Group

801st Torpedo Bomber Group

931st Torpedo Bomber Group

721st Composite Group

171st Composite Group

[650]

In addition, at the outset of the emergency in Kyushu, it was planned to deploy the following units into the area:129

First Air Army

10th Air Division

52d Air Division

12th Fighter Brigade

26th Fighter-Bomber Brigade

Fifth Air Army

53d Air Division

1st Fighter Brigade

2d Fighter-Bomber Brigade

8th Light Bomber Brigade

20th Fighter Group

Third Air Fleet

13th Air Flotilla

8 unnumbered tokko groups

53d Air Flotilla

210th Fighter Group

2 unnumbered tokko groups

71st Air Flotilla

302d Fighter Groups

1 unnumbered tokko group

131st Composite Group

252d Composite Group

601st Composite Group

752d Composite Group

706th Composite Group

Tenth Air Fleet

3 unnumbered tokko groups

2 unnumbered fighter groups

2 unnumbered composite groups

1 unnumbered torpedo-bomber group

In mid July the staff of Sixth Air Army and Fifth Air Fleet conducted a joint operational study in Fukuoka, and during the remainder of the month, both these headquarters perfected their operational plans. Combined and summarized, these plans provided as follows:130

1. Major Objectives

The U. S. convoy will be destroyed by our air forces at approximately the time of its entry into the anchorage. Preparations for this operation will be completed by the end of September.

2. Reconnaissance

a. Naval air forces will be responsible for all long-range, some short-range, and all night reconnaissance.

b. Army air forces will engage in short-range reconnaissance only.

c. Complete reconnaissance coverage of the offshore waters of Japan will be maintained to a distance of 600 miles.

3. Deployment

a. Deployment of all units will be carried out under conditions of extreme secrecy.

b. Initial and reinforcing deployment will be in accordance with the Army-Navy Central Air Agreement of 13 July.

4. Attacks Against Enemy Carriers

a. The enemy carrier task force will not be attacked until it becomes apparent that a full-scale landing is underway.

b. When the above condition is fulfilled, a crack naval air force (approximately 330 aircraft) reinforced by designated army units will attack the carriers and rob them of their ability to support the landings.

5. Attacks Against Enemy Transports

a. When the convoy enters the attack zone, large type transports will be made the targets of a determined, round-the-clock, series of special-attacks.

b. The period of attack will be ten days, during which all available air strength will be used against the enemy.

c. All available fighter strength will be utilised to seize and maintain air superiority over the anchorage area.

6. Attacks Against Enemy Gunnery Ships

Specially trained army and navy air elements (approximately 250 aircraft) will be assigned the full-time duty of attacking ships engaged in naval gunfire support.

[651]

7. Attacks Against Rear Bases

Approximately 1,200 airborne troops will be readied for landings at enemy air bases in Okinawa.

8. Direct Support of Ground Units.

There will be no direct support of friendly ground units on Kyushu.

Operating simultaneously with the air special-attack forces against the enemy were to be the sea tokko units. In the Kyushu and southern Shikoku area, these were as follows:131 (Plate No. 154)

Combined Fleet

10th Special-Attack Squadron

101st Assault Unit132

102d Assault Unit

Sasebo Naval Station

5th Special-Attack Squadron

32d Assault Unit

33d Assault Unit

35th Assault Unit

3d Special-Attack Squadron

31st Assault Unit

34th Assault Unit

Kawatana Assault Unit

Kure Naval Station

8th Special-Attack Squadron

21st Assault Unit

23d Assault Unit

24th Assault Unit

Apart from the sea tokko effort, the naval surface forces were scheduled to play little part in the defense of Kyushu. Most of the vessels of 31st Destroyer Squadron (19 operational vessels in all) were to be used for lifting Kaiten (midget submarine) to the scene of action and for subsequent night action against transports. In consideration of the fuel problem, other gunnery ships were barred altogether from participation in the operations.133

Japan's hope of success in the battle for Kyushu depended almost entirely on the results expected from the air and surface special-attack operations. Even as early as June, the Navy had estimated that about 30-40% of the invading convoy could be sunk by the tokko attacks.134 As reports of the damage inflicted on the enemy off Okinawa in the Ten-Go operation became available for study,135 this estimate was raised to 30-50%. It was estimated that this would cost the enemy at least five assault divisions before the landing even began.136

[652]

PLATE NO. 159

Plan for Decisive Battle on Kyushu

[653]

Although this estimate of enemy losses was officially accepted by Imperial General Headquarters, the Army commanders responsible for the conduct of ground operations within the scope of Ketsu No. 6 recognized that these estimates were excessively high. It was felt that, in view of the difficult conditions under which the tokko operations would necessarily have to be conducted, a more realistic approach to the problem indicated a possible maximum loss to the enemy of 20% of the invasion fleet of transports or about three divisions.137

After receiving this initial setback at the hand of the tokko forces, the enemy was scheduled to meet with strong resistance on the ground from the very beginning of the landings. By the end of July, the tactical commander of ground forces on Kyushu, Lt. Gen. Yokoyama, had at his disposal 14 divisions, six independent mixed brigades, and three tank brigades.138 Although some of these units were still deficient in training, the equipping and deployment of troops were generally completed as was the operational stockpiling of munitions.139

The deployment of major units of Sixteenth Area Army was as follows:140 (Plate No. 159)

Miyazaki-Ariake Bay Area

Fifty-seventh Army-Lt. Gen. Kanji Nishihara

Coastal Forces

Miyazaki Coast-154th and 156th Divisions

Ariake Bay-86th Division

Osumi Peninsula-98th Ind. Mixed Brigade

Mobile Reserve

Kirishima Mt. (Stagingarea)-25th Division, 5th Tank Brigade, one regt., 6th Tank Brigade

Northern Miyazaki Plain-212th Division

Tanegashima Detachment

Tanegashima-109th Independent Mixed BrigadeSatsuma Peninsula

Fortieth Army-Lt. Gen. Mitsuo Nakazawa

Coastal Forces

Makurazaki Coast-146th Division

Kaimon Mt. District-125th Independent

Mixed Brigade

Fukiage Coast-206th Division

Kushikino Dist.-303d Division

Mobile Reserve

Kagoshima area-6th Tank Brigade (less one refit.)

Kirishima Mt. area-77th DivisionNorthern Kyushu

Fifty-sixth Army-Lt. Gen. Ichiro Shichida

Coastal Forces

[654]

Shimonoseki-Moji Area-Shimonoseki Fortress Unit

Fukuma Area-145th and 351st Divisions

Karatsu Area 312th Division

Iki Island-Iki Fortress Unit

Mobile Reserve

Hakata Plain-57th Division and 4th Tank BrigadeCentral Kyushu

Chikugo Group-Lt. Gen. Waichiro Sonoda

Coastal Forces

Nagasaki Area-122d Ind. Mixed Brigade

Oita Area-118th IndependentMixedBrigade

Mobile Reserve-None

Higo Group-Lt. Gen. Ichiji Tsuchihashi

Coastal Forces

Amakusa-126th Independent Mixed Brigade

Mobile Reserve

Kumamoto Dist.-216th DivisionSasebo

Sasebo Naval Station-10 battalions

Tsushima

Tsushima Fortress Unit

Goto Islands

107th Independent Mixed Brigade

In general, the tactics to be used by the ground formations on Kyushu were based upon the concepts which had given rise to the coastal combat and line combat divisional organization.141 These principles applied both to local areas such as Ariake Bay (Plate No. 160), where strong coastal combat formations were backed up by local mobile reserves, and to Kyushu as a whole which was to receive reinforcements from Honshu under the Ketsu-Go plan.142

Salient features of the ground operational plans were as follows:143

1. Theater

a. In southern Kyushu, the principal enemy landing points will be the Sumiyoshi Beach (Miyazaki Prefecture), on the right bank of the mouth of the Hishida River (Ariake Bay), and Fukiage Beach on the Satsuma Peninsula.

b. In northern Kyushu, the principal enemy landing areas will be the Fukuma and Hakata Bay areas.

c. The decisive battle will be sought in the area in which the enemy launches his main effort. If the location of the enemy main effort cannot be determined, the decision will be sought in the Ariake Bay front in southern Kyushu and Fukuma Bay in the case of northern Kyushu.

2. Initial Engagement

In accordance with previously announced tactical doctrine, the coastal combat units, firmly entrenched in large deep cave and tunnel positions and supported by fortress and siege artillery, will immediately engage the enemy close to the beach.

3. Employment of Reserves

a. Success in the battle for Kyushu depends on speed and flexibility in the employment of the decisive battle reserve.

b. As soon as the location of the enemy main effort has been determined, all reserves available in the Area Army will be redeployed to the decisive battle front, leaving the coastal combat units to wage holding actions on the secondary fronts. These decisive battle reserve units will be redeployed through centrally located staging areas from which they can be committed to the battle as preparations are

[655]

PLATE NO. 160

Dispositions in Ariake Bay Area, July 1945

[656]

completed. In the case of southern Kyushu, this will be the Kirishima Mt. area, in the south-central part of the island. In northern Kyushu it will be the Kurume-Iizuka area, in the north-central part of the island.

c. The Area Army mobile reserve, thus constituted at a maximum strength of five divisions and three armored brigades will be later reinforced by the quick arrival of four combat divisions from Thirteenth and Fifteenth Area Armies on Honshu.

4. Missions

a. The missions of Fifty-seventh, Fortieth, and Fifty-sixth Armies are self-evident.

b. Air base troops at Kanoya, Chiran, Miya konojo, and Nyutabaru have the special mission of strengthening anti-ground and anti-airborne positions at their respective installations.

c. Chikugo and Higo Groups located in central Kyushu will keep open the northern and southern approach routes, secure harbors and channels, and wage vigorous holding actions if attacked.

d. The missions of the Sasebo Naval Station Force, Tsushima Fortress Unit, and Goto Detachment are to secure their respective areas and prevent either enemy establishment of forward bases in the vital Korea and Tsushima Straits or break-through in the same sector.